Modeling aneurysm bursts

The Summer Scholars program provides rising juniors and seniors with the opportunity to conduct funded independent research projects as undergraduates. The seven engineering majors who received funding work with their faculty advisors and participate in programming organized by the Office of Scholar Development.

By Isaac Nicholas

Blood vessels and water lines are not so different in the eyes of a mechanical engineer. Both are material structures that facilitate the movement of fluid from one place to another, and both have walls that can weaken over time. While a weakening wall in a water line may lead to a water main break, a weakening wall in a blood vessel may lead to a ballooning artery called an aneurysm – and a ruptured aneurysm is often fatal.

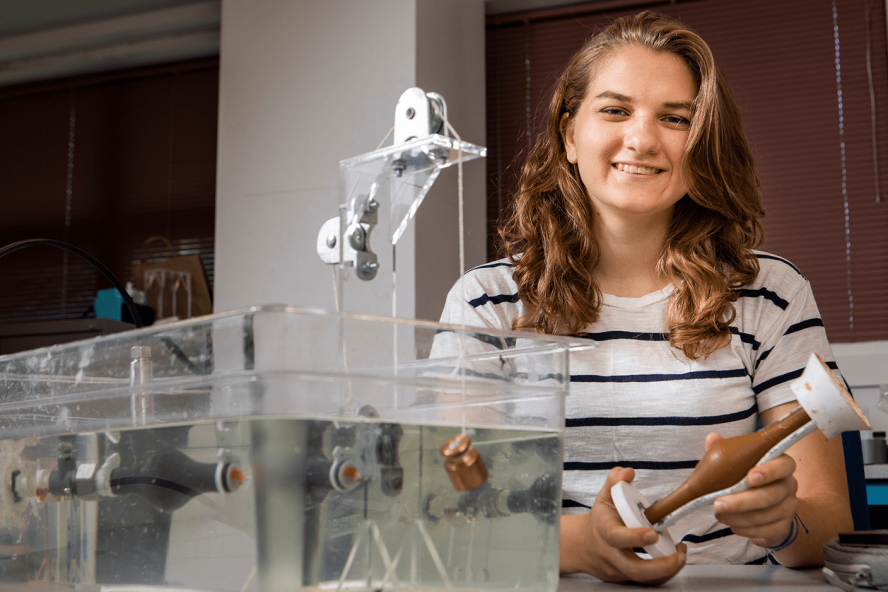

Summer Scholar Taissa Gladkova and Assistant Professor Erica Kemmerling are working in the lab to explore which parameter makes an aneurysm more likely to burst, its shape or its wall thickness. To investigate, Gladkova is making an assortment of life-sized rubber models of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Some models have a bulge while others have no bulge. Within these two general categories, there are models with uniform wall thickness and models with an extra thin wall section.

Gladkova submerges the models in a rig and pumps them full of water until they burst. The team then examines where the burst occurred and gathers insight into the role that shape and wall thickness played in the rupture. The goal of the research to identify the characteristics of an impending rupture and to provide metrics that can help doctors determine if invasive surgery is required.

Early results indicate that large variations in wall thickness matter, while smaller variations don’t play as much of a role in affecting the bursting behavior. Gladkova and Kemmerling plan to conduct more tests to verify these results and to determine how much variation is tolerated before increasing the likelihood of a rupture.

The team experienced some minor setbacks with their early models, but Kemmerling has been encouraged by Gladkova’s perseverance throughout the project. “You can’t work through things [in the lab] in a linear fashion like you do when you’re doing coursework, so I think that this is part of the learning process in Summer Scholars,” says Kemmerling. “Stuff breaks all the time in research, and Taissa has been doing a great job of handling that.”

Gladkova has found this work to be a valuable dive into research and what it means to do research in an academic context. She is learning how to manage her own experiments and gaining experience on physical equipment as opposed to running simulations on a computer. She has developed the skills to excel as an independent researcher, but she also recognizes that there are times when collaboration with more experienced engineers is necessary. “I’ve learned to ask for help and that it’s okay to ask for help,” says Gladkova.

Gladkova believes the Summer Scholars Program is an excellent program for undergraduates who are passionate about something, but don’t necessarily have a way to make it happen on their own. “It gives them the opportunity to do research and the resources needed to support them,” she says. She plans to use her own experience to propel her forward towards a master’s degree and her career. “Summer Scholars has helped to put things into perspective about what my options are,” says Gladkova.

Department:

Mechanical Engineering