Learning from human-robot conflict

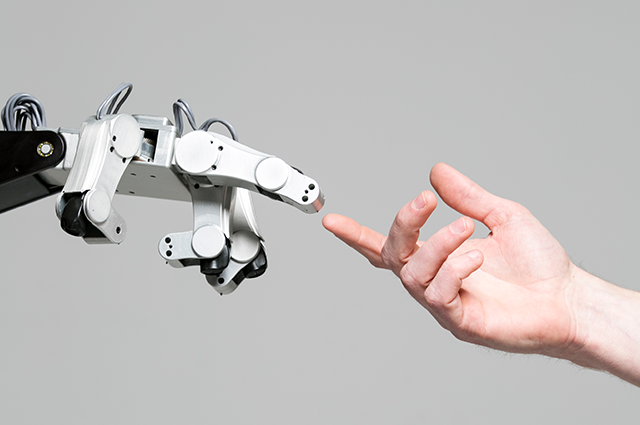

From virtual assistants to assistive technology and smart devices, robots are becoming increasingly prevalent in everyday life. With increased human-robot interaction comes a higher potential for conflict, but a group of researchers including Assistant Teaching Professor Dave Miller and Professor of the Practice James Intriligator, both of the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Tufts University, believe that may be a good thing.

Miller and Intriligator worked with faculty from the University of Central Florida and Stanford University to present their work on human-robot conflict at the recent Robophilosophy 2022 conference in Helsinki. The research was published in the journal Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications in an issue titled “Social Robots in Social Institutions.” Their paper, “Social Robots in Constructive Conflicts,” explores the potential of making low-level human-robot conflict as maximally beneficial to both parties as possible.

Human-robot conflict is multifaceted and can involve fault on either side. According to the researchers, most of the issues stem from a mismatch in the robot’s capabilities and the human user’s expectation of the robot’s capabilities. The design of the robot can lead to user error if it is not clear how to operate the robot in the desired manner. For example, a person may set their toaster to a setting that they think will produce the perfect golden-brown toast but become frustrated when the toast comes out burnt. The toaster is performing the task it was assigned, but the user misunderstood the settings. Robots typically have limited flexibility in their actions and struggle to adapt in the face of human conflict. A toaster would not be able to predict the exact kind of toast a user wants; it can simply take commands from the user and produce results based on its programming.

As in human relationships, the researchers argue that some low-level conflict between humans and robots is important to help strengthen their relationships. Many human-robot conflicts result in some form of coercion, either on the robot’s part by forcing the human to accept what it’s offering, or on the human’s part by turning off the robot. Instead, the researchers call for a middle ground in which humans and robots can compromise and adapt to conflict situations. To that end, they emphasize the need for designers to include conflict resolution mechanisms in the design of robotic systems.

Faculty across the School of Engineering continue to pursue research and advancements in the relationship between humans and technology. Assistant Professor Jivko Sinapov of the Department of Computer Science recently received a CAREER Award from the National Science Foundation for his work developing a method for robots to share acquired knowledge with one another. Intriligator’s research lies at the intersection of technology design and consumer psychology. Miller focuses on human-technology conflict and the distinctions between proactive agents and reactive agents. He has also received a Tufts Wittich grant to support a student researcher this coming summer.

As the technological complexity of robots and their capabilities grows, Miller questions, “What happens when a technological agent or robot contradicts you? Or crimps human autonomy, even if ultimately for the best?” Miller, Intriligator, and others in the Tufts School of Engineering and across the globe consider questions like these in their research as technology continues to evolve.

Department:

Mechanical Engineering